Ando Hiroshige, Plum Tree Garden at Kameido, 1858. From his final woodblock print series, 100 Famous Places in Edo.

Say the word PRINT and you realize that it means different things to different people. The outcome of photography is a print. The output of the machine in your home office is a print. Numerous images such as posters might qualify as prints. While technical and aesthetic skills may be visible in these prints, they generally are characterized by industrial smoothness and anonymity. In contrast, the FINE ART PRINT is a work that has a lot in common with painting—conceived and achieved by the vision and talent of an artist whose hands are involved all the way to completion and exhibition. The big distinction between a FINE ART PRINT and a PAINTING is that the act of painting results in a single tangible outcome—paint on paper or fabric—whereas the FINE ART PRINT is produced by a process that is intended to make MULTIPLES. Depending on the process, the quantity varies from a dozen to hundreds of prints, usually nearly identical to one another. Knowing about the processes of printmaking can enhance one’s appreciation of their unique properties and, depending on the process, their rarity.

For me, some of the pleasure in experiencing prints comes from the effort to connect the print’s appearance with the process by which it was made. A great book for beginners that uses this very approach is How Prints Look, by William Ivins, one of the great print curators who studied prints for 30 years at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Contemporary fine art printmakers may combine processes or work experimentally, but prints of 100 years ago or longer usually provide clear examples of the artist working with just one process.

Edouard Manet, Portrait of Charles Baudelaire en face, 1865 (etching, part of the French “etching revival” of the 1860s).

Another source of pleasure in experiencing prints comes from the realization that the print on my wall has belonged to others in the past, and other impressions of it belong to other people right now. I know that museums and collectors own other impressions of my print, making me a member of a club of worldwide appreciators of that image. The ease with which prints can and have circulated through time has given them special significance for the transmission of visual ideas—art historian Leo Steinberg, who sold his great print collection (3200 or more) to the University of Texas, argued that the portability of prints, plus their existence as multiples, made prints the “circulating lifeblood of ideas.” Ownership of a fine art print puts in the owner’s hands a piece of visual history with vastly greater potential than its humble existence as a sheet of paper might suggest.

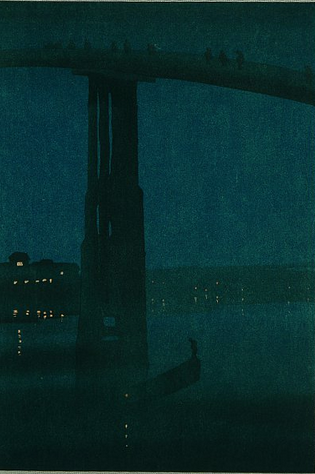

Anonymous, Misty Bridge at Night, c. 1930. A woodblock print by a Japanese artist, reproducing the fragment of the Battersea Bridge that had been painted by James McNeill Whistler (titled Nocturne: Blue and Gold—Old Battersea Bridge, c. 1872 under the influence of the very popular Japanese woodblock prints he was collecting at the time).

So these pleasures are both sensual and intellectual—prints require extra time to perceive what is on the sheet and to recognize and appreciate the link between process and product. Prints can be windows into the past, able to awaken the owner to historical events; or offer glimpses into lives lived long ago; or celebrate perceptions of the real world that we still appreciate today.

Karen Pope, PhD, taught art history at Baylor University until 2015, collecting prints to enrich the classroom experience.